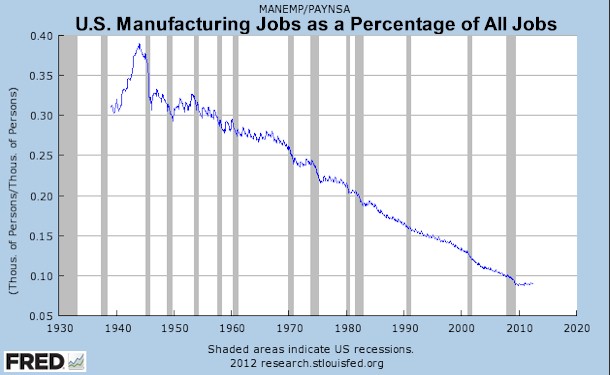

The graph below, based on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, shows manufacturing employment in the United States as a fraction of all employment. As you can see, the line heads downward in an almost perfectly straight line beginning in the mid-1950s. Notice that the line doesn't become steeper as globalization takes hold after the passage of NAFTA in 1994 or the rise of China over the past decade or so. The line just slopes consistently downward.

This is primarily the result of technology, and in particular, automation. Manufacturing in the U.S. has become dramatically more productive and requires fewer workers. If we were to graph manufacturing output (rather than jobs), the line would slope upward, not downward. The value of U.S. manufacturing production is now far greater than it was in industrial era of the 1950s, even after adjusting for inflation. We just make all that stuff with a lot fewer people.

One of the most interesting things about the graph above is that, if technology is the primary driver, then employment in China must inevitably follow the same path. In fact, there are good reasons to believe that manufacturing employment's downward slope will be significantly steeper for China. The U.S. had to invent the technology to make manufacturing more productive, while in many cases China only needs to import it from more developed nations. It is also true that China is beginning its journey at a time when information technology (which is the primary enabler of automation) is many orders of magnitude more advanced than in the 1950s when U.S. manufacturing employment was at its peak. (See this

recent article on skilled robots from the

New York Times).

In the U.S. (as well as in other advanced countries), workers shifted out of manufacturing and into the service sector -- which now accounts for the vast majority of jobs. Will China be able to pull off the same transition?

The U.S. had the luxury of building a strong middle class during an earlier time. Technology was advancing consistently and increasing productivity, but it was not so advanced as to create a mismatch between the type of available jobs and the skills of workers. Unionization was strong in the private sector and helped ensure that the lion's share of productivity increases ended up in workers' (rather that corporate owners') pockets. Those workers, in turn, became the broad-based consumer class that purchased the output from all those factories and kept the overall economy humming.

The situation in China is quite different. Consumer spending accounts for only about a third of China's GDP (as opposed to 60% or more in nearly all developed countries). While China has built a significant middle class in absolute terms, it remains small as a percentage of the country's huge population.

Workers enjoy few of the rights and protections that characterized the U.S. workforce of the 1950s. As I wrote in my book,

The Lights in the Tunnel:

The [Chinese] government actively enforces discrimination that tends to drive wages even lower. Much of the work in China’s factories is performed by migrant workers who officially live in the countryside but are allowed to come to cities or industrial regions to work. These workers typically live in factory dormitories and do not have the right to bring their families to the cities or to genuinely assimilate into an urban middle class. Wages for these workers are far lower than for urban dwellers, and the money that they do earn is for the most part either saved or sent home to help support their families. These workers are not in a position to become major drivers of local consumption any time soon.

According to the

New York Times, those worker dormitories apparently play an important role in Apple's (or Foxconn's) ability to bring production online at

any time of the night or day:

A foreman immediately roused 8,000 workers inside the company’s dormitories, according to the executive. Each employee was given a biscuit and a cup of tea, guided to a workstation and within half an hour started a 12-hour shift fitting glass screens into beveled frames. Within 96 hours, the plant was producing over 10,000 iPhones a day.

Even that level of worker availability and efficiency isn't enough for Foxconn, which recently announced the introduction of

huge numbers of robots. That may be a great way to drive production, but it's hard to see how China will succeed in dramatically shifting its economy toward domestic consumption.

And that has to happen before a shift to a service economy can take place. As consumers become more wealthy they begin to spend a larger fraction of their incomes on services -- things like banking, insurance, healthcare, education, entertainment and travel -- and that in turn drives service sector employment. At least that has been the path followed in other developed countries.

In the absence of consumer spending, China's economy remains highly dependent on manufacturing exports and, especially, on fixed investment. An astonishing 50% of China's GDP is driven by investment in things like factories, housing and infrastructure (the U.S. figure is around 15%). The problem is that all that investment has to ultimately pay for itself, and that happens via consumption. Once a factory is built it has to then produce something that gets sold at a profit. Homes, retail buildings and apartment complexes likewise have to be

sold or rented out. Obviously, no economy can indefinitely invest anything like 50% of its output without eventually finding a way to get a positive return on that investment.

Achieving that return requires consumers -- either at home or abroad. China continues to rely heavily on consumers in the U.S. and Europe, but that's unlikely to be a sustainable formula for growth. The debt crisis and the resulting austerity is cutting into economic growth and consumer spending in both Europe and the U.S.

As manufacturing automation increases (perhaps dramatically) in China, in the U. S. and other developed countries the most disruptive impact from technology will be in the service sector -- where millions of white collar jobs and service jobs in retail, distribution, food service and other areas may ultimately be at risk. After all, if robots can build an iPhone, then its a good bet that they will also someday be able to

build a hamburger or mix a latte. The result may be continuing high unemployment, stagnant wages and tepid consumer spending throughout much of the developed world.

The real problem China faces is that it is late to the party. Just as it reaches its manufacturing employment zenith, it faces a potentially disruptive impact from automation technology. And that will happen roughly in parallel with similar transitions in the service sectors of the countries that currently consume much of its output. In the face of that, can China succeed in re-balancing its economy toward consumption, increasing personal incomes, and building a vibrant service sector to keep its population employed?